19 Introductions and Identifying the Rationale

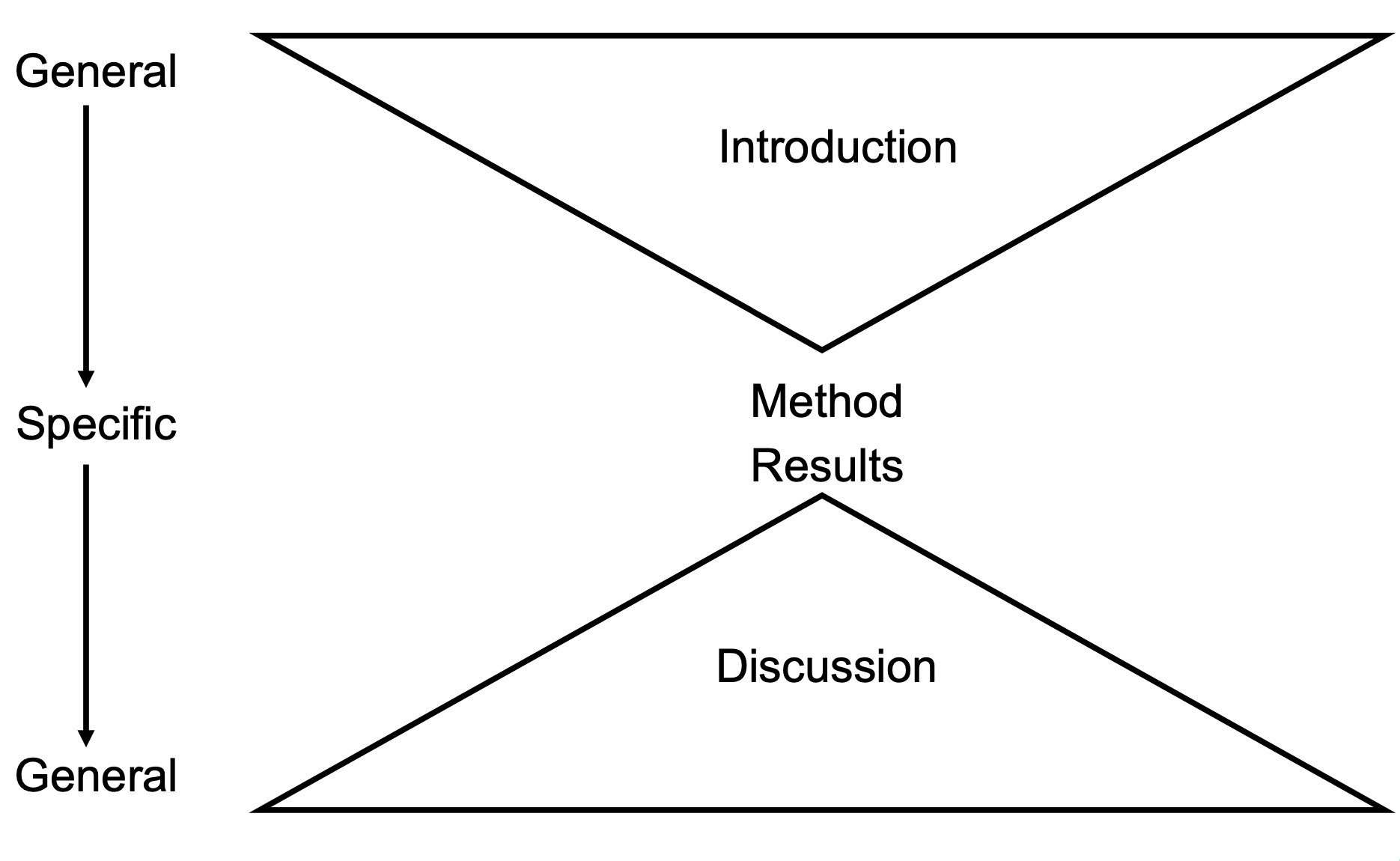

Now we have introduced you to the idea of an empirical quantitative research report, we will spend most of the semester breaking down specific sections or skills that go into a report. Empirical psychology articles follow a roughly standardised approach resembling an hour glass. The main sections include an abstract, introduction, method, results, and discussion.

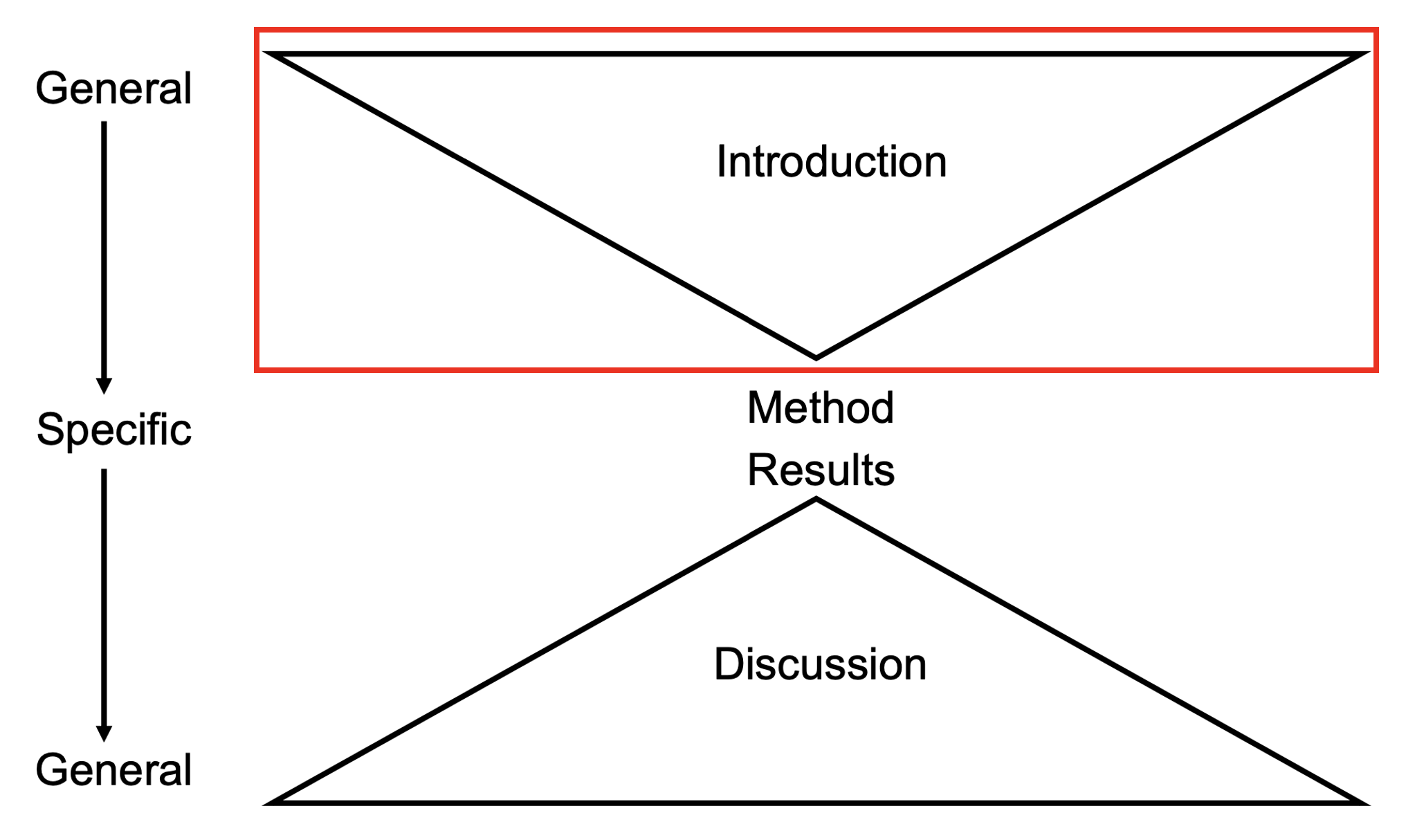

In this chapter, we are focusing on the introduction as the first major section in a report (Figure 19.1). The abstract technically comes first, but given it is a summary of your whole report, you typically write it last, so we will save that for later.

19.1 The introduction

The introduction provides the background to your study for what influenced your work. Relating back to the hypothetico-deductive model, the introduction focuses on the cycle between previous research and identifying your research question. You need to know what research and theory already exists before you can identify an opportunity for your own work. There are four key components:

Introduction to the general topic and research question.

Evaluation of relevant research and theory.

Establish a rationale for the current study.

Present the research question and hypothesis (where applicable).

The introduction is the top of the hourglass shape of a report, starting broad and becoming more specific as you get closer to the end (Figure 19.2). You do not typically have sub-headings to present these components as specific sub-sections or dedicate just one paragraph to each part, rather they are key concepts to cover as you move through the introduction.

19.1.1 Introduction to the general topic and research question

The opening paragraph or two to the introduction is the broadest section. We are at the top of the hourglass and this is where you introduce your reader to the key concepts. You are trying to provide the rationale behind your overall topic, so you might include statistics to highlight the extend of a given problem. You might also present definitions for key concepts to make it clear to your reader what you are researching. This part of the introduction is all about setting the scene to your reader and establishing why it is a topic worth addressing.

19.1.2 Evaluation of relevant research and theory

The literature review should provide a critical and focused exploration of your topic area. You do not need to try and summarise all the research that has ever been done on your topic, you are trying to identify what is most relevant and up-to-date.

Critical evaluation is an important skill that takes time to develop. Instead of just listing and describing the studies in your literature review, you must add narrative and identify gaps in current knowledge. Try and ask yourself as you are documenting the studies you find:

Are the findings consistent across studies, or do they provide a more complicated mixed picture?

All studies are not created equally, each will have their own strength and weaknesses. You do not need to walk through the strengths and limitations of each study, but you will make an assessment on how reliable you consider the evidence base to be.

Is there a relevant theory or framework that explains the observations of previous research? Do the studies support this theory or suggest there are limitations?

19.1.3 Establish a rationale for the current study

By the end of the introduction, you are trying to clearly communicate what opportunity you have identified in past research and present your argument for why it is important to address that opportunity. This is the rationale as the reasoning behind why your study is necessary. Sometimes the opportunity is to explore something new, other times you could identify limitations in past research that need addressing. There is not one single valid approach to the rationale, it all depends on the strength of your argument you presented throughout the introduction.

To show the range of possibilities for the strategy behind your rationale, we wrote a specific section and activities on identifying the rationale below.

19.1.4 Present the research question and hypothesis

The final part of your introduction should be a summary of what you want to find out in your study (your research question) and what you predict you will find based on previous research (your hypothesis). The most effective introductions will present a clear narrative from the start to the end, so the reader can almost guess what your rationale, research question, and hypothesis is before you tell them.

Depending on the aim of your study, remember a research question is essential, but a hypothesis is not. If your study is exploratory, there might not be enough research to make a prediction, so the aim of your study is gather evidence. If you study is confirmatory, there will be a larger research base and the aim of your study is to test a specific prediction.

19.1.4.1 Research questions

Research Questions (RQs) are broad overarching questions of interest. They are posed literally as questions and summarise what you hope to answer through your study. Research questions should be:

Clear: specific enough to be understood without further explanation.

Focused: narrow enough that you can answer it with your project.

Complex: there is enough discussion to create a report out of it.

Concise: to the point so it is more likely to be understood.

Arguable: there is not already a clearly accepted answer and there is a rationale for your project, regardless of whether it is more of a novel approach or it is a direct replication of one specific study.

It is crucial to base your research question on previous research. Make sure you have read enough to pose your research question as you need to know what is already out there before you can present the rationale for your study.

An example of a poor research question could be: Do undergraduate students suffer from text anxiety? It is quite vague and the context is unclear for what is being compared and how. A better research question could be: Do undergraduate students self-report greater test anxiety than postgraduate students? This is more focused on the actual research at hand, showing who you are comparing and giving more detail on what you want to measure.

19.1.4.2 Hypotheses

Hypotheses are specific statements making a prediction for what you will find. Hypotheses should be:

Clear: you can easily understand the statement.

Specific: you cover all the key information, such as who, what, and how.

Falsifiable: you should be able test the prediction to show how evidence either supports or refutes it.

Operationalised: to state how you are measuring your constructs.

To break down these features, we can start with a good example of: We hypothesise that there will be a positive correlation between effort regulation scores and help-seeking scores in mature students, as measured through the MSLQ. We can then manipulate different features for emphasis:

Missing operationalisation: We hypothesise that there will be a positive correlation between effort regulation scores and help-seeking scores in mature students.

Not testable: We hypothesise that there might be a positive correlation between effort regulation scores and help-seeking scores in mature students.

Not a hypothesis: Is there a positive correlation between effort regulation and help-seeking?

Depending on how much previous literature is out there and how convinced you are by it, you can pose a directional or non-directional hypothesis. A directional hypothesis makes a prediction in a specific direction, for instance group A will be faster than group B. On the other hand, a non-directional hypothesis predicts there will be an effect, but it is not clear what direction it will be. For example, the speed of group A will be different to the speed of group B.

You might pose a non-directional hypothesis for exploratory research to help your focus. For confirmatory research, you should be able to specify a clear directional prediction to test.

19.1.4.3 How does this relate to your stage one group report?

For your stage one group report, you will be focusing on either the relationship between two variables or comparing the difference in one outcome between two groups. Depending on which approach you and your group are taking, the terminology you use for the research question and hypothesis will differ.

Correlations assess whether there is a relationship between two variables. You might have a non-directional prediction where you think two variables are correlated, but you are not sure how. Alternatively, you might have a directional prediction where you expect a certain correlation direction. Positive correlations are where if one variable increases, the other variable tends to increase. Negative correlations are where if one variable increases, the other variables tends to decrease. If some of the terminology is unfamiliar to you at this point, we do not cover correlations and continuous predictors until week 7 after reading week.

In contrast, comparing groups assesses whether there is a difference between two groups on your outcome. If you have a non-directional hypothesis, you think there might be a difference between the two groups, but you are not sure which direction. If you have a directional hypothesis, you expect one group to score higher than the other group. You will learn about t-tests and categorical predictors for the analysis techniques suited to this kind of research question in week 8.

19.2 Identifying the rationale

Now we have introduced the key components of an introduction, we want to spend a little more time on different strategies for the rationale. As much as we would love to just tinker as scientists, each study tries to address some kind of problem the authors have identified in previous research. These are often small tweaks. Keep the phrase “standing on the shoulders of giants” in mind as science typically advances through minor changes rather than completely revolutionary ways of studying a topic. Approaches for the rationale will differ by discipline and sub-discipline but there are some common strategies you can look out for.

In this section, we have provided seven examples of the rationale from different empirical psychology articles, including exploration, replications, testing competing theories, applying the methods from one study to a new sample/population or topic, and addressing limitations in past research. The rationale should be built as a thread running throughout the introduction as you narrow down to what your study focuses on, but we have isolated paragraphs that specifically comment on the opportunity they have identified. For each example, we have explained the general approach, provided an extract, and described in our own words the authors’ line of argument.

At the end, we have some activities to test if you can recognise different strategies. By the end of this resource, you will be able to identify different strategies behind the rationale in published research and hopefully clearly communicate the rationale in your own reports.

19.2.1 Exploring an under researched topic

Although completely novel research is rare, there are times when there is little knowledge about a population or topic. For example, there might be a change in practice or a cultural phenomenon that means you have little prior research to turn to. This means your study would follow more of an exploratory approach to gather information and learn about a new population or topic.

Example: Beaudry et al. (2022, pg. 2) were interested in what incoming undergraduate students knew about open science practices. Moving out of the replication crisis, increasing numbers of researchers adopted open science practices and more journals were encouraging or enforcing them. As this was a rapid shift in how researchers conducted studies, Beaudry et al. explored undergraduate students’ beliefs about open science practices as they had little prior research for this cultural shift.

“…An understanding of contemporary methodological practices—and problematic methodological practices—is essential for becoming informed and critical consumers of psychological knowledge. Studies have explored strategies for educating psychology students about replicability and open science practices (e.g., Chopik et al., 2018; Grahe et al., 2012; Jekel et al., 2020). These initiatives may help ingrain open science norms and change attitudes about research practices, but we know little about what students know or believe about open science research practices prior to entering the university classroom. This knowledge could be useful for two main reasons… [two paragraph gap]

To examine this, we conducted a descriptive study, asking incoming students in undergraduate psychology courses about their beliefs regarding reproducibility and open science practices. Our survey encompassed questions concerning norms (how students felt research should be conducted), norms in practice (how students believe psychological research is conducted), and replicability (how replicable students believe psychological research is). Our study was exploratory (see Wagenmakers et al., 2012) and descriptive; as such, we did not specify or test hypotheses.”

19.2.2 Direct replication of a previous study

Authors can argue it is important to verify the results of a specific previous study. This means they would use the exact same method as the target study but in a new sample to find out if you can get the same results. The rationale for a direct replication often explains why it is important to replicate individual studies in general or why the target study should be replicated. For different features of a study you might highlight to motivate a direct replication, Alister et al. (2021) polled researchers on features that would increase or decrease their confidence in replicating the study’s results.

Example: Micallef and Newton (2022, pg. 2) investigate the use of concrete examples in learning abstract concepts. Their article is a direct replication of a specific study they highlight. They explain Rawson et al. is an influential study but other research questions the consistency of the findings, so they want to replicate their method as closely as possible to see if they get the same results.

“Thus, the evidence base for the use of concrete examples in teaching would appear to be mixed. Given the potential significance of Rawson et al. for the teaching of psychology, but set against some mixed findings from other studies, we tested the replicability of the key finding from Rawson et al. Rawson gave their participants definitions of some abstract ideas from psychology, followed by multiple different concrete examples of those ideas. A control group received only the definitions, repeatedly. Both groups were then tested to determine whether they could match examples to definitions. The group which had received the concrete examples were better able to match definitions to examples including, critically, examples that they had not previously seen. Rawson et al. suggested their study was amongst the first study of its kind to use a ‘no-example’ control group, a design which considerably strengthened the conclusions but highlighted the paucity of well-controlled research into the application of this idea to learning and teaching, and further emphasised the need for replication of the findings from this key study.”

19.2.3 Conceptual replication of a previous study

Whereas a direct replication wants to copy the method of a study as closely as possible, a conceptual replication tries to test the same idea or hypothesis using different methods (Nosek & Errington, 2017). The aim is to find out if you can make similar conclusions under different methods and increase your confidence in an explanation or theory of human behaviour.

Keep in mind there is a continuum between a direct and conceptual replication. It comes down to judgement and subject expertise on what differences would turn a direct replication into a conceptual replication. For instance, Lebel et al. (2018) present a replication recipe where authors rate their methods as exact, close, or different on features including measures, procedure, and location.

Example: Ekuni et al. (2020, pg. 5) wanted to learn about study strategies in a different population. They highlighted previous studies focused on US American samples which tend to be relatively higher in education level and socioeconomic status than some other countries. Therefore, they took the method of Karpicke et al. (2009) - a US-based study - and applied it to a sample in Brazil to investigate if they could find a similar pattern of results.

“This is even more important in countries in which educational outcomes are poorer than those in the U.S. and in which the need for interventions that can help improve academic success and reduce educational inequities is dire (see UNESCO, 2015; Master, Meltzoff, & Lent, 2016), such as Brazil. To do so, it is necessary to carry out a conceptual replication on preference of study techniques in more diverse non-WEIRD contexts to analyze whether culture of origin, SES, and sex can influence students’ study strategies, because designing adequate interventions may have to consider tailoring to fit particular characteristics of different types of students.”

19.2.4 Testing competing theories or conflicting research

As you research a given area, you recognise patterns across the findings of articles. Imagine you are studying the effectiveness of an intervention treatment compared to a control treatment. Do all the studies show the intervention works, do most studies show the intervention works, or is there completely mixed evidence on whether the intervention performs better than the control? If there are conflicting findings, then the aim of your study could be to add more evidence.

Relatedly, there might be competing theories on the same phenomenon. One theory might expect participants to score higher in one condition compared to another, while another theory expects participants to score higher in the other condition. This means the aim of your study could be to find out which theory is best supported.

Example: Bartlett et al. (2022, pg. 2) combined both components after observing some studies showed daily smokers’ attention would gravitate towards smoking images more than non-daily smokers, whereas other studies showed the opposite pattern. There were theories which could support each observation, so Bartlett et al. aimed to test which theory and pattern of results would receive the most support.

“…Collectively, these studies show that smokers consistently display greater attentional bias towards smoking cues than non-smokers, but it is not clear whether lighter or heavier smokers show greater attentional bias.

To address this inconsistency, the current study focused on comparing attentional bias towards smoking cues in daily and non-daily smokers. While most studies use the visual probe task to measure attentional bias, their relatively small sample sizes and inconsistent research design features complicate drawing conclusions from the mixed findings. Therefore, we used a much larger sample size than previous studies and manipulated different features of the visual probe task.”

19.2.5 Applying the methods of one study to a new sample/population

It is important to consider whether your planned measures and/or manipulations are valid and reliable. This means you could identify components of the method you consider robust in previous research, but you apply them to a new sample or population that would let you address your research question.

This is similar to the argument in the conceptual replication example, but there is a subtle difference in the aims of the approach. In a conceptual replication, you want to know whether you can find similar results using different methods. The emphasis is on comparing your findings to a target study to see if they are similar or different. On the other hand, in this approach, you want to learn something new by applying methods from one study to a new sample. The emphasis is on addressing a new research question using methods that have a precedent in past research.

Example: Veldkamp et al. (2017, pg. 128/129) investigated the storybook image of scientists in scientists themselves. In their introduction, they outlined studies on the general public’s perception of scientists’ characteristics like honesty and objectivity. However, the authors explained they were unaware of similar research of scientists’ perception of scientists’ characteristics. This means they were applying methods to a new sample that was previously under researched.

“…More recently, European and American surveys have demonstrated that lay people have a stable and strong confidence both in science (Gauchat 2012; Smith and Son 2013) and in scientists (Ipsos MORI 2014; Smith and Son 2013). For example, the scientific community was found to be the second most trusted institution in the United States (Smith and Son 2013), and in the United Kingdom, the general public believed that scientists meet the expectations of honesty, ethical behavior, and open-mindedness (Ipsos MORI 2014).

As far as we know, no empirical work has addressed scientists’ views of the scientist. Although preliminary results from Robert Pennock’s “Scientific Virtues Project” (cited in “Character traits: Scientific virtue,” 2016) indicate that scientists consider honesty, curiosity, perseverance, and objectivity to be the most important virtues of a scientist, these results do not reveal whether scientists believe that the typical scientist actually exhibits these virtues…”

19.2.6 Applying the methods of one study to a new topic

Related to the previous strategy, you might not have a new sample/population you want to learn about, but you might want to apply the methods of a past study to a new topic. For instance, your research question might focus on alcohol but previous studies you are aware of might have used smoking images. The emphasis in this strategy is that you want to learn something new by applying the methods of one study to a different topic.

Example: Irving et al. (2022, pg. 2) studied the effect of correcting statistical misinformation. Making causal claims about correlations is a common mistake in science journalism when you lose some of the nuance of full journal articles and the authors wanted to know if you could correct that statistical misinformation. Previous studies had corrected other types of misinformation using this technique, but Irving et al. wanted to know whether it would be effective in reducing statistical misinformation. This means they applied the method from one study to a new topic it had not been used on before.

“In this study, we applied the continued influence paradigm, which has traditionally been used to examine general misinformation, to a novel context. We investigated whether it is possible to correct a common form of statistical misinformation present in popular media: inappropriately drawing causal conclusions from correlational evidence. Participants were randomized to one of two experimental conditions: no-correction or correction. They read a fictional news story about the relationship between extended TV watching and cognitive decline, inspired by an article in The New York Times (Bakalar, 2019). Informed by previous research, we designed the correction to be as powerful as possible. We therefore included an alternative explanation, in recognition of the fact that individuals prefer to maintain a complete but incorrect model of an event until they are given an alternative explanation to sufficiently fill the gap left by a simple negation (Lewandowsky et al., 2012). Similarly, we ensured that the correction was from a credible source, that it maintained coherence with the story, and explained why the misinformation was inaccurate (Lewandowsky et al., 2012). The primary, confirmatory hypotheses were that participants in the correction condition would make fewer causal inferences (i.e., rely on the misinformation) and more correlational inferences (i.e., rely on the correction) than those in the no-correction condition, in response to the coded inference questions.”

19.2.7 Addressing limitations in the method of a previous study

Every study has its strengths and weaknesses, the important thing is being able to justify your choices and acknowledge the limitations. One set of researchers might value a tightly controlled environment at the expense of a more realistic but messier environment, whereas you value a more realistic environment. In this strategy, your research question aims to learn something new by designing a study that addresses the limitations you identify in a past study.

Example: Bostyn et al. (2018, page 2) were interested in the classic trolley dilemma where participants have the option of letting a tram run over five people or intervene and divert the tram so it runs over one person. Often, this is only a hypothetical dilemma, so the authors wanted to create a more realistic version. Instead of choosing to divert a tram, participants were faced with the option of shocking a cage of five mice or intervening and shocking a cage containing one mouse (the participants were unaware the mice would not actually be shocked). This means the authors wanted to investigate if participants would behave similarly in a more ecological valid task.

“Until recently, this judgment–behavior discrepancy has been an academic concern plaguing only moral psychologists. However, trolley-dilemma-like situations are becoming increasingly relevant to model the moral decisions of artificial intelligence, such as self-driving autonomous vehicles (Bonnefon, Shariff, & Rahwan, 2016). Accordingly, whether or not hypothetical moral judgment is related to real-life behavior is prone to become a matter of public interest. We are aware of one study that has directly compared hypothetical moral judgment with real-life behavior: FeldmanHall et al. (2012) found that people are more willing to harm others for monetary profit in a real-life scenario than they are in a hypothetical version of the same scenario, thus confirming that real-life behavior can differ dramatically from hypothetical judgment. The current research was a first attempt to study this difference in the trolley-dilemma context through the admission of a”real-life” dilemma that required participants to make a trolley-dilemma-like decision between either allowing a very painful electroshock to be administered to five mice or choosing to deliver the entire shock to a single mouse.”

19.2.8 Summary

So far, we have outlined the strategies behind the rationale from a selection of empirical psychology articles. This is not an exhaustive list, but we wanted to demonstrate the common lines of argument researchers take when explaining what opportunity they identified in past research and how their studies will address that opportunity.

It will be rare for studies to neatly fit into just one strategy. They might focus on one component or it might be a combination. Bostyn et al. (2018) addressed limitations in past research but you could also argue it was a conceptual replication by using a more ecologically valid task to see if they could observe similar findings to studies using hypothetical tasks. Likewise, Bartlett et al. (2022) tested competing theories, but also wanted to address limitations in the method of past studies.

The important lesson to take away from this is to clearly communicate your line of argument behind the rationale of your study. By the end of your introduction, it should be clear what opportunity you identified in previous research and why it is important for you to address that opportunity with your study.

19.2.9 Activities

Now that you have read about different strategies for a rationale and explored different examples, it is time to see if you can recognise key features of these strategies yourself. Remember, these are broad descriptions to capture the main features and there are many ways of presenting your argument for the rationale.

19.2.9.1 Independent judgement 1: Muir et al. (2020)

In the following extract, Muir et al. (2020) explain their study on promoting classroom engagement through the use of an online student response system.

As you read through the extract, consider and select which strategy you think best fits their rationale. After selecting the type of rationale you think best fits, check the explain the answer box to see why we placed it there.

“The use of Socrative has been investigated across a variety of disciplines including physics (Coca and Slisko 2013), physiology (Rae and O’Malley 2017), science (Wash 2014), sports management (Dervan 2014), computing (Awedh et al. 2014), English language (Kaya and Balta 2016), economics (Piatek 2014), and engineering (Dabbour 2016). Statistics courses are another area that may benefit from using Socrative given its potential positive effect on the student learning experience and considering that course evaluations by students taking statistics units tend to indicate poor engagement (Gladys, Nicholas, and Crispen 2012). To the authors’ knowledge, only one study has previously investigated the effect of Socrative specifically for statistics students. Balta and Guvercin (2016) found that the final grades of students enrolled in a statistics class who chose to engage with Socrative-based learning materials prior to their exam were significantly higher than the grades achieved by students who chose not to engage with the Socrative-based learning materials. Although this result is encouraging, the use of a non-randomized, post-test design means that we cannot confirm from this study that there is a beneficial effect for using Socrative, or if the difference in exam scores was due to underlying scholastic aptitude or motivation of the students who chose to engage with the OSRS. Hence, there is a need for further research exploring the use of Socrative specifically within statistics classrooms”

In this article, the authors highlight there is one key article that studied a previous topic but they identified several flaws in the method that affect the conclusions. The earlier study by Balta and Guvercin (2016) uses a non-randomised post-test design which is prone to confounds and you cannot make a strong causal conclusion. In the next paragraph not shown here, the authors explain their study will target these limitations by randomising participants into conditions.

19.2.9.2 Independent judgement 2: Harms et al. (2018)

In the following extract, Harms et al. (2018, pg. 2) explain their study on the rounded price effect.

As you read through the extract, consider and select which strategy you think best fits their rationale. After selecting the type of rationale you think best fits, check the explain the answer box to see why we placed it there.

“In recent years, studies from nearly all subfields of psychology have been under increased scrutiny in the context of the ‘replication crisis’ [2-5]: as several studies suggest, we cannot take reported effects in the scientific literature at face value. As the findings by Wadhwa and Zhang have practical relevance to marketers, independent replication of the effect and a reasonable estimation of its size are desirable. From the theoretical outline of the effect one can expect the effect to be contingent on various factors. As a first step towards a better understanding of these external influences on the effect, a close replication under the same or at least very similar conditions as in the original study is warranted.”

Hopefully, this was quite an obvious one. The authors mention a few times they want to replicate the rounded price effect that was first observed in Wadhwa and Zhang. They justify the direct replication by explaining it has practical implications to marketers and want to repeat the study as close as possible to the original methods.

19.2.9.3 Independent judgement 3: Rode and Ringel (2019)

In the following extract, Rode and Ringel (2019, pg. 320) explain their study on comparing the use of R and SPSS software in introductory statistics courses.

As you read through the abstract, consider and select which strategy you think best fits their rationale. After selecting the type of rationale you think best fits, check the explain the answer box to see why we placed it there.

“Professors of courses without lab components, and/or courses in which students have high levels of statistics anxiety and diverse mathematical and computational backgrounds, may be left wondering whether it is worthwhile to introduce students to R over other software types. Indeed, ongoing debates in online education communities suggest that the use of R with undergraduates, and how the experience compares to teaching software such as SPSS, is very much an open question that many educators would like to see answered empirically (e.g., see https://www.researchgate.net/post/Is_it_easier_for_students_to_learn_statistics_using_SPSS_or_R). Statistics professors have likewise written blogs about the benefits and drawbacks of R and SPSS (e.g., Anglim, 2013; Franklin, 2018; Wall, 2014). These debates capture the concern that R is a highly useful program for students but comes with a steeper learning curve and fewer resources available for beginners compared to other software, leading instructors to question whether it is wise to emphasize R in an introductory course (especially those for non-statistics majors). To the best of our knowledge, no study has explicitly compared the teaching of R to statistical software more commonly used with undergraduates, such as SPSS. Moreover, there is little research on incorporating statistical output in the introductory classroom, much less whether one type of output is more advantageous than another.”

The key details are in the final two sentences to explain they are not aware of past research comparing the software and they want to explore this under researched topic. Previously, Rode and Ringel discussed statistics anxiety and the use of different software to teach introductory statistics courses. However, they were not aware of previous studies that compared software and investigated whether one was better than the other.

19.2.10 How does this apply to my stage one group report?

Now you have read different strategies and worked through activities to identify potential arguments for the rationale, you can think in your group what your line of argument will be. As you conduct your literature review for the introduction, you will start to develop a sense of what research is out there on your topic and what research is missing.

For example, there might be research on test anxiety and self-efficacy in isolation, but maybe there are seemingly no studies looking at the direct relationship between them. You might find lots of research looking at the relationship between intrinsic motivation and age in undergraduate students, but maybe there are no studies on postgraduates. There is one key study comparing meta-cognitive self-regulation in undergraduates and postgraduates, but it has not been independently directly replicated.

The strategies for the rationale above was not an exhaustive list, so do not worry if your rationale does not neatly fit into one of these categories. There is not one correct approach as it will depend on how you present the literature review and work towards the gap you identified in past research. By the end of the introduction, it is just important to clearly communicate and justify your rationale to the reader so they can see your line of argument.